In his book El Terreno en disputa es el lenguaje (Language is the disputed territory), José Ignacio Padilla asks of the poem’s raw material: is it the sound, the pneumatic breath, the paper, the ink, the writing? The title of the present text supposes a response to that query and stakes out a position in exploring the distinct transformation of the word in the poem, understood as a fundamental element with which the latter is constituted.

How is and how does a word occur in a poem?

It’s worthwhile to distinguish between two different levels of materiality of the word--those which constitute, we should note, two poles that operate within the poem: the graphic or spatial, on one hand, and the sonic or temporal, on the other. The first level implies a textual base, a determined trace, at times present in the typography. Here, for example, we can see the way that the words “stone” and “Stone” are by no means identical. Beyond distinctions between the letters in manuscript, printed, or virtual form, the iconographic level of the word is much more relevant in poetic discourse than in other contexts [1]. The acoustic dimension similarly fulfills a fundamental role in the poetic experience as a word that is concrete, spoken, or just an acoustic image (for example, in quietly reading to oneself). Thus, the phonemics of the word ‘stone’, notably the occlusives, count in the poem.

Beyond the tension between virtuality and the concretion of both levels of the world, I will allow myself to work through five moments of the poetic experience. It would be fitting to add that should it engage a presupposition of historicity, the weaving and unweaving of the poetic text does not imply in any way a teleology, nor, for that matter, anything akin to an “evolution”. On the contrary, it assumes the possible coexistence of these moments-as they, in effect, coexist today- as moments that cover distinct aesthetic ranges, even while woven together by the same weft.

Moment Zero

It’s largely commonplace to assign both poetry and music the same origin. To allude to a time in which both activities were essentially one and, as a kind of addition, to desire that time when both lines might return to their source. It has been insisted that the concretion of the voice, at times understood as the raw material of poetry, has an inherently musical character: it delineates a tone, it rings with a certain timbre, it lays claim to a rhythm in its futurity. It is impossible to pronounce, to mark out syllables, to articulate, to stutter and to not inscribe oneself in the temporal horizon of music.

Nevertheless, I want to insist here, that that moment in which music and poetry were not brought back together, but were, rather, the same thing, that instant is imaginary. The first moment is, then, a non-moment; a situation that doesn’t have a concrete existence but, instead, one might say, a mythical one. At the root of that divergence -and from here on the ethical and aesthetic consequences of the position that I assumed at the beginning of the essay will become clear – is the word. The word, the clay of the poem, cannot ‘leave off’ signifying something, although that something can, at times be an unsaying, a mutilating of its own communicative capacity; in the same manner, sound, musical material, cannot signify [2]. That basic dialectic, that hybrid forms can traverse (the sound poem that shifts into babble, music that becomes song and accommodates the word), defines, from this perspective, both activities and establishes tensions within its own internal mechanism. Thus, the music of the western academy has been able to create narrative effects in certain pieces, above all when it makes reference to a concrete situation. [3] Thus the verbal usage in the mystical tradition tends to defamiliarize language and loosen its bonds with the signified, in the knowledge that in itself the existence of the word is both vehicle and postponement of such a longed-for experience.

If this de-linking of music and poetry can seem a bit arbitrary, as it is natural for us to encounter both forms as a single conjuncture, I perform it as a means of destabilizing an initial divergence (or what amounts to the same, it affirms the sole imaginary existence of that non-moment), though not, thus, the impossibility of then re-linking these two manifestations. When Verlaine proclaimed, with millennia of poetic tradition at his back, de la musique avant tout chose, he was evidently establishing a utopia. The symbolists’ bet on musicality doesn’t offer us the ancient contest between signifier and signified thus reviving what exists in poetry precisely in its tending toward the dissolution of the communicative faculty, toward the conversion of the word to phoneme and the phoneme to mere in-significant sound. From there, when the meaning of a poem is unclear, we feel propelled toward an appreciation of its sonic qualities; and thus, when we hear a language that we don’t understand there is a tendency to appreciate its musicality – the melodiousness of the vowels, the percussiveness of the consonants.

From this perspective, the music is “anterior” to the poem like non-verbal languages to verbal ones. The existence of music, or of a temporal auditive plane, is the condition for the emergence of the word, which is sound but is not solely so. The beginning was not in the verb.

Moment One

“Sing o muse[MOU1] ”

This is the beginning of the first canto of the first poem of the western tradition: with an invocation of the word, of the sung word. The listener, who is slowly enveloped by the poem, is not a witness to the Achaeans who suffer on the battlefield, nor do they follow Achilles in his desperate pursuit of Hector, nor, in one of the most famous descriptions of literature are they capable of seeing the designs on the hero’s shield. The listener only listens to the word of the rhapsody or, from the perspective of the rite, to the muse herself who speaks in an alien language. In Moment One, only the voice has materiality and is inscribed on the time-horizon, which is to say, it is ephemeral; the image/imagination only exists, in the listener’s mind’s eye. One does not see the muse, but does, certainly, hear her.

It is not, then, surprising that what remains for us of the Homeric poems, of the medieval epics or of the Provencal songs are a pale translation of that experience. Nonetheless, certain textual marks make evident a utilization of those linguistic resources that corroborate not only the musical dimension, but the visual, too. In oral poetry, for example, the repetitions or the choruses that beyond reinforcing the motives of the poem can function as a mode of amplifying the voice. Devices like the epithet, according to Borges, fulfill a mnemotechnic function in the Greek epic. The oral poet, whether already a joglar or traversing the contemporary city, enters the sonic dimension and his instrument, the voice, must be adapted in order to be an efficient medium for what surrounds him and which he cannot control: he competes with the sounds of other instruments, not always played by him, and with the soundscapes of nature, machines, and people. There is no blank page that delimits an inviolable and secure space. Here the poem lives with the world.

However, the voice does not appear separately from a body and that body, in turn, from a concrete situation in the world. Thus, the experience of the listener (spectator?) is unique, unrepeatable, auratic. The paradigm of this first moment is the theater, though a theater-it must be specified-that requires the word. Stripped of the elements that are secondary to it (props, scenery, etc), the essential characteristics of the theater are the same as those of oral poetry: the scene, none other than “empty space”, and the relation that exists between the actors (the oral poet) and the public [4]. The reading of an oral poem omits the possibility of appreciating that relationship between the actor and public; moreover, it gives the impression, false in many cases, of being a transcription of a monologue or dialogue. The writing fixes a “standard” version of the poem, nearly an abstraction of itself, that necessarily impoverishes it. In stripping away all the “impure” elements of the execution, it abandons all that which for the staged arts (theater, dance, music, oral poetry) is essential and indistinguishable from the “pure”.

Of course there is one element that alters many of these coordinates: that which Benjamin called the technical reproducibility of the art object. For example, does the work of the recent Nobel winner in literature, Bob Dylan, and more generally that of whatever contemporary singer-songwriter, form part of this first moment? My impression is that it does not. The vehicle between Dylan’s work and the spectator, listener, reader are media of mass communication. The coexistence has disappeared in the majority of the cases (how many Nobel jurors or fans have heard Bob Dylan live?); thanks to the printed texts that accompany CDs as well as those that exist on the internet, one can come to the oral word of the singer-songwriter with the written word, which do not always coincide. The voice and the body continue to be fundamental, but they are mediated by the recording console or the documentarian’s camera. The track or the film can be corrected ad infinitum like the painter who retouches his painting or, better yet, the writer who reworks their lines. Here the poem no longer coexists with the world; the camera or the console are their blank page.

Moment Two

The objections that the Greeks had toward writing are well-known. In the Phaedrus, Socrates-who, as opposed to Plato, did not write-notes some of them: the text’s inability to respond to the reader’s questions, the multiplication of misunderstandings (a consequence of the preceding) and the abandonment of the mnemonic exercise while the people would begin to become dependent on the written. Lesser known are those texts like the Doric inscription in Sicily, which reads: “He who writes these words will penetrate the anus of the one who reads them” [5]. The conditions of writing-the scriptio continua or phonetic rather than etymological writing-made the process of reading a complicated activity, and one performed audibly. In Ancient Greek, reading was an activity linked to passivity; it was an activity reserved for slaves who read for their masters; the prestige of writing could not compete with that of the oral word. Nonetheless, Plato himself wrote the teachings of his master, and although the problems of philosophical interpretation of the Platonic corpus seem to credit Socrates (was the former truthful to this latter’s postulates or, in short, can one trust the written text in spite of its being “mute”?), this fact reflects the same necessity that impelled Pisistratus a century earlier to demand the copying of the Homeric cantos: to fix the text, to revoke the ephemeral quality of orality [6].

Thus, the originating function of writing among the Greeks was a means of containing a discourse whose nature was, essentially, oral. The conception of the written poem in Moment Two is not all that distinct, if in time its oral actualization terminates in silent reading. Text, from that perspective, is insufficient, as the poem is not there; its letters are a cipher, a conjuncture of signs that permit its invocation. The only material dimension of the word is the graphic/written/scripted one, but to this is denied whatever inherence it has in the aesthetic experience. The poem occurs through an invocation of both a visuality and a sonority, which in the text only exists in a latent sense.

A major portion of the western lyric tradition is circumscribed by these coordinates. When the critic affirms that Gongora is a plastic, graphic poet, he is speaking in metaphoric terms. Nothing in the Soledades assigns a visual experience, per se; although it may appear obvious, Gongora’s poetry does not appeal to our eyes but to our imagination. In that punctual aspect, it cannot be differentiated from the description of Achilles’s shield in earlier Moment; only the imagination-not understood in opposition to reason, but rather in its first meaning, as a ‘faculty of representing images of real or ideal things’- can make us experience the poem. In 1849, a young Gustave Flaubert could still read the manuscript of The Temptation of Saint Anthony out loud to Louis Bouilhet and Maxime Du Camp, which allowed them to critique his precious style and urge him to write about contemporary themes from which Madame Bovary resulted. For Flaubert, the method par excellence for testing a work was still oralization.

In Moment Two, writing has neither autonomy nor value in itself: it is a code, perhaps a medium, whose sole function is to replace the absent voice. Its paradigm is sheet music. Its materiality, the paper, the typographical conventions, all of it exists as a facilitator of a single purpose: its reading.

Moment Three

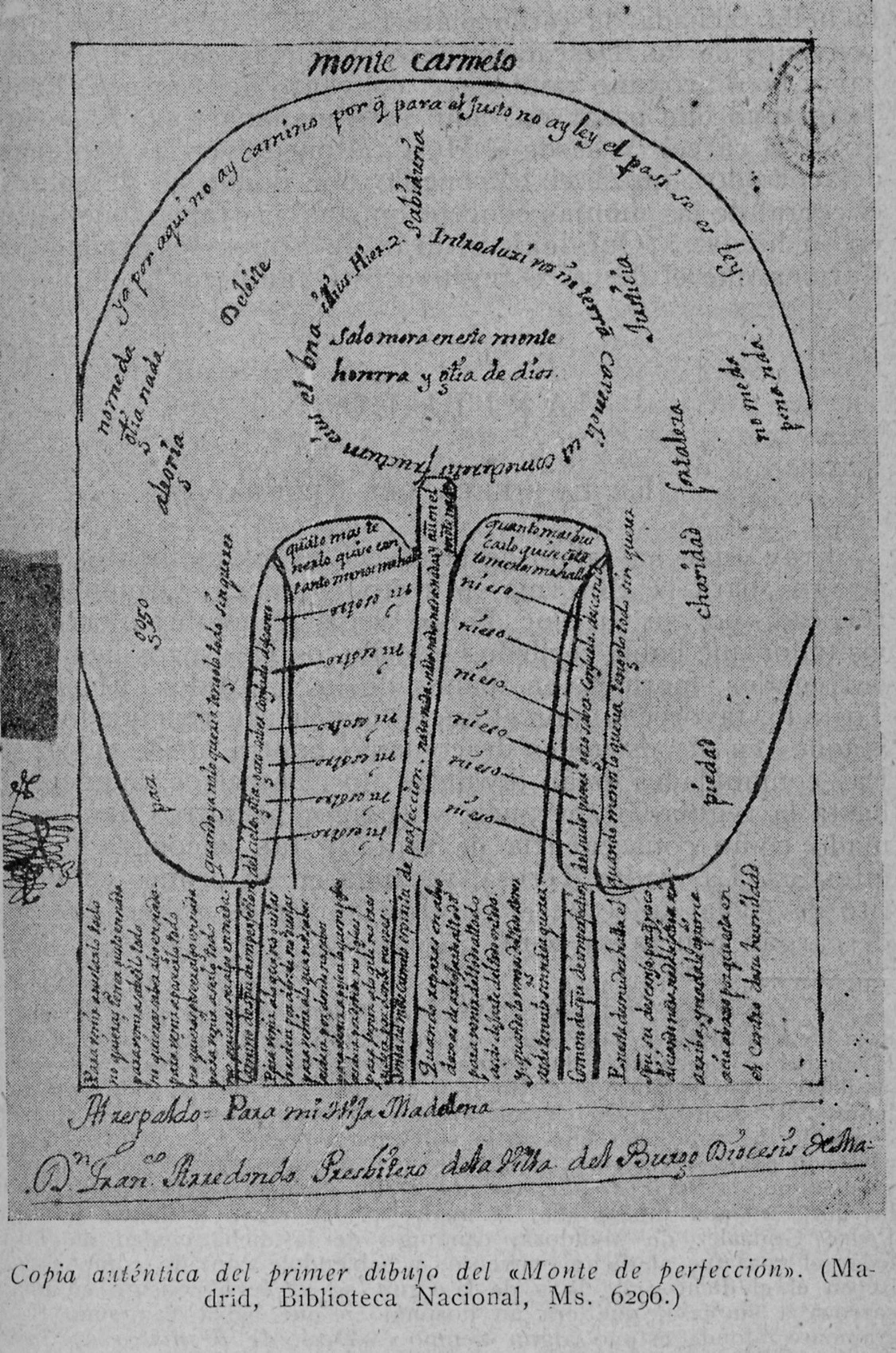

While walking one March night in 1897, Paul Valery arrived at the idea that the universe could be a text in which he was caught. He was accompanied by Stephane Mallarme, both smoking, on their way to the train. The latter had, earlier that evening, shown Valery the corrected proofs of a publication that would change the destiny of western poetry, Un Coup de Des. Valery would later write a chronicle in which he would compare the poem with the ‘writing’ of the constellations. This isn’t difficult to imagine. The poem uses the freedom of the blank page’s space, breaks with traditional grammar and typographical conventions, as in its varied font sizes; the words are displayed entirely freely like the stars in the text of the night sky. If it can be said that it doesn’t lack for precedents – I am thinking of poems by Simias de Rodas or in the autograph manuscript of the poem “Monte de Perfección” by San Juan de la Cruz -, Mallarme’s poem signifies an awareness of the expressive possibilities of the blank page that would have a profound effect on the following century, whether in the calligrams of Apollinaire or in Brazilian concrete poetry, to cite two well-known examples.

Mallarme’s mark would be felt not only on the level of visual poetry but also in apparently more traditional poetry. After Un Coup de Des and the avant gardes, a new means of understanding poetry emerges: the visual condition of the poem. The graphic materiality of the word extends into a dimension that did not exist before and, even if the sonority of the poem itself – which was always virtual given its dependence on the reading process to flower – was still maintained, from that moment in which reading aloud became incapable of recreating the aesthetic experience. There is an analogous relationship between Moment One and Moment Three with Moment Two: if the oral poem is necessarily impoverished as it passes into writing, the visual poem that incorporates visual elements also loses some of its constitutive elements on moving into orality. The image, real and concrete, is already part of the poem.

The existence of the visual levels in the poem – one, material and graphic; the other, imaginative, that of the “plasticitiy” of Gongoran poetry – allows for the initiation of new tensions. In some cases, the poet will look to tautology (word and image refer to the same object); in others, divergence (cf. the final verse of “Poetry in the form of a bird” of Eielson). The counterposing of image and word, between seeing and reading, also interests visual artists, as is evident in the celebrated Ceci n’est pas une pipe by Magritte.

An author who was preoccupied by the formalizing of the technical aspects of this new poetry was Charles Olson, most notably in his celebrated essay Projective Verse. His opposition to the metrical verse would be impossible without the discovery of the visual side of the poem. Olson valorized the possibilities that the typewriter gave the modern writer, like the employment of other typographical signs and the greater precision in inserting spaces into the poem. Still, it is surprising that his vision of the poetic text remains undergirded by the parameters of Moment Two. The American poet, drawing from his great antecedents – Pound, Cummings, Williams-, proposes the use of the typewriter “as a scoring to his composing, as a script to its vocalization”. For Olson the technological innovations do not change the condition of the poetic text, they only change its precision. This carries with it certain futile operations like trying to determine how long the reader need wait on arrive at specific punctuation (commas, dashes) or blank space.

Olson’s own poems themselves are most adept at debunking his own earlier postulates. Many of The Maximus Poems are irreducible to oral recitation, due to their use of different typefaces, the capricious placement of some words and the incorporation of signs and icons in the text itself. Olson and the great majority of the poets of the 20th century write poems whose spatial disposition lay claim to another means of approximating the poem. If it follows that some of them incorporate the concrete image, in the majority of cases space permits them to constitute another syntax, parallel to the grammatical, that allows us to speak of a visual rhythm in the poem. Thus, the paradigms are visual artists and, in to some extent, advertising discourse. [7]

Moment Four

In a scene from J’ai tué ma mère (2009), the debut film from actor and director Xavier Dolan, the protagonist, Hubert, says goodbye to his professor. The latter knows that Hubert will not return to high school and that perhaps he will not see her again, as, rejected by his parents, he has been enrolled in a boarding school. She knows that Hubert is on the brink of broaching a question and that, in a certain way, what he is waiting for is a descent into hell. Thus, before he goes, she takes a book by Musset from her library and indicates a page and a strophe that he should read. Upon doing so, she says that he should leave her house; the reading, one understands, must be done alone. In the next shot, the adolescent walks down a street with the open book, the pages blown by the autumn wind. Later, he stands against a wall, aligned left on-screen, while on the opposite side the strophe from Musset appears, which makes reference to the relationship between a mother and son.

The director’s solution here is particularly effective, as while the viewer reads the romantic poet’s verses they can appreciate Hubert’s gestural, corporeal expression. They are likewise unable to listen to the verses read in off – perhaps in the voice of the protagonist, of the professor, or of the mother-, in such a way that it would ‘contaminate’ the scene, which requires silence for an appreciation of its particular intensity. The words, which appear as subtitles, invade the screen, making evident the rupture of the verisimilar pact between the auteur and the spectator: what the latter sees is not reality, the camera is not the eye of a witness, but rather a conventional mode of scaling, mediating a conjuncture of signs, an aesthetic experience. It emphasizes the ‘artificial’ facet of cinema, to the detriment of its mimetic dimension.

In addition to the intertitles, which are common in silent cinema, letters traditionally encroach on the screen and the image at one specific moment: the credits. The impression that the spectator traditionally has is that the credits do not constitute a part of the work; they are alien to it like the page that contains the editorial details of a text. Nonetheless, a range of directors have been able to give life to this ‘dead’ moment, inserting them into the film’s plot. [8] In some cases, the presentation of the credits allows for a creative use of the word – I am thinking about the beginning of Godard’s Pierrot le Four – that adds an aesthetic dimension to that which, in another mode, would be a mere formality.

All of this is relevant because, at the end of the 20th century, some creators began to explore the aesthetic possibilities of the word in a completely distinct medium: the audio-visual. In general, the development of cinema – which today has displaced the novel as the omnivore’s art par excellence, that which can be incorporated by other artistic manifestations – has modified our mode of encountering the artistic act. The experience fostered by the final minutes of Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev or in much of Wim Wenders’ Pina or Fernando Trueba’s Calle 54, if essentially cinematographically, are also incursions into the language of painting, dance, and music respectively. The resources of audiovisual and cinematographic media have opened a wide range of aesthetic experiences linked to poetry and the word, from the recording of a reading or the animation of a poetic text (as has been done with the poems of Billy Collins) to the creation of an autonomous audiovisual object. Given the condition of technical reproducibility of the audiovisual, these forms can be combined with performance, which creates still more possibilities and in a sense, presupposes a return to the theatrical level of oral poetry from moment one.

One specific form that has been charged by an unusual impulse with the development and popularization of digital media is the video poem, whose paradigm – and of the entirety of this moment in general – is the cinematographic. Its central elements are the confluence of image, sound, and word, with the latter serving in its double materiality. That is, as an acoustic and graphic phenomenon. It is here, as much as in Moment One, that the pronounced word returns to the poem. Still, the differences are notable: on being reproducible ad infinitum, on being fixed, and being unwaveringly identical to itself, the voice is inscribed in a technological context alien to its initial aural dimension. For its part, the employment of the graphic also contrasts with the earlier two moments. In contrast to painting, written poetry or advertising, the words of the video poem – as in the examples of Dolan and Godard – are unstable. Their fleetingness lies in the special limitations of the screen, capable of simultaneously holding a much smaller number of signs than the pages of a book. [9] What is lost on the spatial plane is gained, nevertheless, in the temporal; in cinematographic language the written word is homologous to the ephemerality of the spoken word.

Still from Arnaldo Antunes, Pessoa

Tom Konyves, a pioneer of the genre, is the author of “Videopoetry”, a manifesto that seeks to define its scope and possibilities. A rapid excursion through the web allows one to note not only the range of possibilities which the videopoem offers, but also that these are easier to theorize than to bring into practice. That is not surprising: videopoetry still has to invent a tradition and to create a public. The work that our era has grown accustomed to and which bombards our audiovisual discourse can be seen to bear greater familiarity with, though also greater estrangement from, our artistic appropriation of that language. All the same, two facets appear in Konyeves’s manifesto having to do with the appreciation (listening? Reading? Visualization?) of some video poems. The first has to do with the retreat of the written word. The conditions of the medium itself, the fleetingness of the sign and the simultaneity of diverse stimuli, augur that the utilization of the letter will have to contain itself, given that sustained reading, understood in a traditional sense, is made more difficult. That can signify an approach to iconic possibilities of the word already described in Moment Three. On the other hand, this is a second feature, as for the first time the two levels of the materiality of the word, the graphic and the acoustic, coincide in the poem, and likewise coincide in the confluence with other images and other sounds. As Konyves notes, it is not in the tautological relation of said levels, but also in their disparity, where the possibilities of the density of this genre are to be rooted. A fascinating example of this divergence is the video poem Pessoa by Arnaldo Antunes. There, while the words scroll quickly across the screen, the voice of the poet simultaneously pronounces their grammatical categories, which makes the ‘reading’ of the text noticeably more difficult (but does the video poem need to be read?) The two ‘narratives’ coincide at times– the grammatical category ‘subject’, with ‘Pessoa’ written on the screen, for example - , but the broader effect of the poem transcends this situation; in a certain sense, the voice desacralizes the written poem, it objectifies it, it reduces it to being solely the condition of linguistic structure.

With the development of the internet, the possibilities of the composition of the video poem are notably heightened, while this does not exclude the fact that the web is today also the favored space for the distribution of texts from other poetic moments. As much online as offline, in the world, this means the conflictive coexistence of heterogenous forms, where the poem is almost always asphyxiated by a series of signs with which we are bombarded. To know how to live inside or outside of the poem is, more than ever, understanding how to read those signs.

Notes:

If not exclusive to poetry. For example. At the moment of writing a political harangue, it is common to do it in capital letters so that it will have the greatest emphasis. This use of typeface is still more evident in the language of marketing. Its influence on certain portions of 20th century poetry has been well-documented.

Except when it is a word, but in that case it is no longer treated solely as a sound. Throughout history, music has incorporated the word, whether sung or spoken (as in the recitative of opera and other forms of western classical music). I am not taking up this sort of confluence in the present text.

For example, in the 1812 Overture, which commemorates the Russian resistance to the Napoleonic invasion. The cannons, a common go to in this sort of music, seek to emulate the atmosphere of battle. Later they were included in parts of La Marseillaise that presumably represent the arrival of the invading army. In both cases, its mimetic intentionality is evident.

As to this oration, I am alluding to the approaches taken by Jerzy Grotowski in his classic essay Towards a Poor Theater.

I am taking from Jesper Svenbro’s essay Greece: Archaic and Classical: The Invention of a Silent Reading, where the author writes that “to read was here, was, then, to find oneself with the paper as the passive, discounted, partner: while the writer was thought of as the active, dominant, valued partner” (in History of Reading in the Western World, p. 70-71

Although this would lead to more “oral readings”. The idea of the text, independent of its moralization, is almost absent in Ancient Greece. I defer, again, to Svenbro’s essay.

During the period of the historical avant gardes, the book also stops being understand as mere surface and acquires a physical, concrete dimension (for example, in the book objets), a process analogous to what happens in the visual arts in works like those of Marcel Duchamp. In that sense, Moment Three doesn’t take as paradigmatic the traditional visual arts.

Two examples from two very different films. While Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) features credits after the first scene, which function as a sort of prologue, Haneke’s Caché (2005) does so at its close. In the latter case, the letters’ background is the scene which continues on.

Unless these are superimposed, which impedes their own legibility. That it is what Arnaldo Antunes does in his video poem, Nome.

Https://issuu.com/tomkonyves/docs/manifesto.pdf